A mental illness can be defined as a health condition that changes a person’s thinking, feeling or behavior (or all three) and that causes the person distress and difficulty functioning.

Historically a distinction was made between mental illness and other brain or neurological disorders such as epilepsy, Multiple Sclerosis, Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer’s, etc. However, through ongoing investigation of the brains’ of individuals with mental illness scientists are discovering that mental illness is associated with changes in the brain’s structure, chemistry and function and that mental illness, like physical illnesses, has an underlying biochemical or physiological dysfunction. 1

Epidemiology

Recent estimates report about 20% of Americans, or about one in every five adults, suffer from a diagnosable mental disorder. Additionally, in the U.S., four of the ten leading causes of disability are mental illness: major depression, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia and obsessive-compulsive disorder. Further demonstrating the impact of mental illness on Americans, about 20% of doctor’s appointments are related to anxiety disorders, such as panic attacks. 1

Understanding Brain Function

The brain is a highly complex organ. Although it only makes up about 2% of body weight, it uses 20% of the energy we take in through food and the oxygen we breathe.

The brain is responsible for nearly everything we experience as humans; every thought, action and behavior involves communication between nerve cells, also known as neurons, that are triggered by special chemicals called neurotransmitters. Hundreds of thousands of these chemical reactions occur every second in the brain.

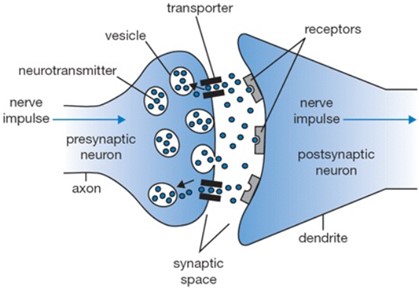

Neurons are the functional units of the nervous system. They are specialized cells that can communicate with one another using electrical and chemical signals at junctions called synapses. At a synapse one neuron, a presynaptic neuron, sends a message to a target neuron, a postsynaptic neuron. There is no physical connection between the two neurons at the synapse, rather it is an intercellular space known as a synaptic space (or synaptic space). An average neuron forms approximately 1,000 synapses with other neurons. Synaptic connections are constantly changing as new synapses are created or existing synaptic connections are reinforced and strengthened in response to stimuli/life experiences. These change in neuronal connections is the basis of learning.

How Neurons Communicate

A message sent from one neuron to another requires an electrical impulse/signal trigger that causes a chemical change within the cell stimulating vesicles within the neuron to release their contents, neurotransmitters, into the synaptic space. These neurotransmitter molecules drift across the synaptic space and bind to receptors on the postsynaptic neuron causing an electrical impulse signal within the postsynaptic neuron. Once the neurotransmitter stimulates an electrical impulse, it releases from the receptor and moves back into the synaptic space to be taken back into the presynaptic neuron via transporters or reuptake pumps and repackaged in vesicles to be released with the next electrical impulse. Neurotransmitters not taken back up into the presynaptic neuron are degraded by enzymes in the synaptic space.

There are a variety of neurotransmitter molecules utilized by the nervous system but each neuron specializes in the production and release of a single type of neurotransmitter. Some of the predominant neurotransmitters in the brain include glutamate, GABA, serotonin, dopamine and norepinephrine. 1

Many experts now attribute an impairment in neurotransmitter function to mental illnesses. Inflammation, hormone imbalances, poor blood glucose regulation and nutritional deficiencies are some of the factors that can impair neurotransmitter function.

Risk Factors for Mental Illness

Some factors that have been identified as increased risk for mental illnesses include environmental (such as head injury, poor nutrition and exposure to toxins), genetic, and social.

Although a history of emotional or physical trauma and poverty increases the likelihood of mental illnesses, scientists discovered that the greatest predictor of mental illness was not life experience but rather a family history of the disorder. Through ongoing investigation most experts agree the primary cause of mental illness involves genetic or acquired chemical imbalances that change brain function. In particular, most mental disorders involve imbalanced levels or altered functioning of critically important brain chemicals, neurotransmitters. 2

To date, most research has focused on a few neurotransmitters that have been associated with thought function. For instance, low serotonin activity has been linked with depression, excess norepinephrine is linked with anxiety and elevated dopamine with schizophrenia.

Often overlooked are the primary raw materials in the synthesis of many neurotransmitters, nutrients such as amino acids, vitamins, minerals and other biochemicals obtained from food. As an example, serotonin is synthesized from the amino acid tryptophan while requiring vitamin B6 as a co-factor in the production process. And dopamine is produced from tyrosine and requires folate and iron. Additionally, B6 and zinc are necessary for the production and regulation of GABA. 2

It has become clear that inappropriate levels of key nutrients can have an adverse effect on brain function and mental health. As a result of these alterations some individuals have a predisposition for conditions such as depression, OCD and ADHD, while others are quite invulnerable to these disorders. 2

A variety of genetic and environmental abnormalities can create nutrient imbalances in the brain. This understanding has led to a new approach in the treatment of mental illnesses called biochemical therapy or nutrient therapy. The goal is to carefully identify specific nutrient overloads and deficiencies of an individual and provide nutrition therapy to precisely normalize blood and brain levels of these chemicals.2

Benefits of Biochemical Nutrition Therapy 2

- Optimizing the levels of nutrients needed for neurotransmitter production

- Epigenetic regulation of neurotransmitter activity using targeted nutrient therapy

- Reducing free-radical oxidative stress

Biochemical therapy can be used together with medication and counseling, providing great flexibility to the mental health practitioner and individual. 2

Diet and Mental Health Impacts

Fat Imbalance

The brain has a very high fat content (about 60%); therefore, the fats consumed directly affect the structure and substance of the brain cell membranes. Unsaturated fatty acids (PUFA and MUFA) are especially important because they provide fluidity to cell membrane and assist in the communication between brain cells. At brain synapses, four essential fatty acids (PUFAs) make up more than 90% of the lipid content: docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), eicosatetraenoic acid (EPA), arachidonic acid (AA) and dihomo-gamma-linolenic acid (DGLA). Of these DHA, an omega 3 essential fatty acid, is found in the highest concentration and seems to have the greatest impact on brain function. Followed in priority by EPA, another omega 3 essential fatty acid. Fatty cold-water fish such as salmon, mackerel, anchovies and sardines are great sources of these essential omega-3 fatty acids. AA and DGLA are essential omega 6 fatty acids and are typically at excessive levels in individuals who consume junk food. A healthy balance of Omega 6 to Omega 3 intake is ideally about 3:1. 2

In contrast saturated fats, those that are hard at room temperature, make the cell membrane in our brain and body tissue less flexible. Additionally, trans-fat is of particular concern because of its ability to distort cell membranes and alter the ability of neurons to communicate. Essential fatty acids are converted in the body through a series of reactions into DHA and EPA. Trans fats however block this conversion by competing for the same enzymes needed for this conversion. As a result, these vital nutrients, DHA and EPA are not available to support brain function effectively. Trans fats are found in processed foods like commercially-made baked goods and prepared meals. 2,3

Glucose dysregulation

A significant number of individuals with mental health illnesses exhibit chronic low blood glucose levels.2

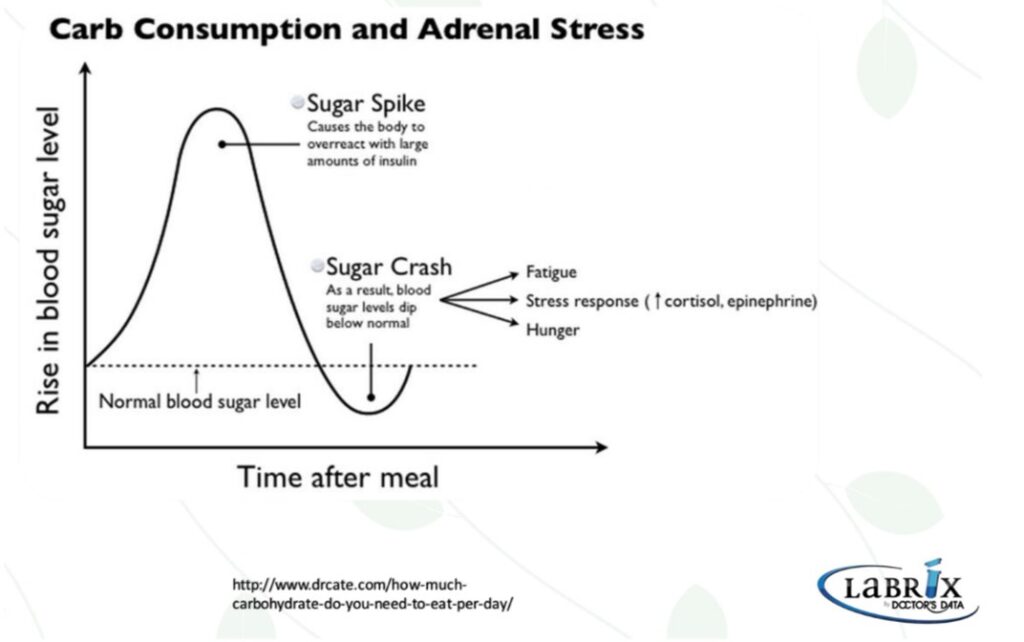

The brain’s primary fuel source is glucose; it uses more of this nutrient than any other organ in the body. Glucose/sugar is derived from the carbohydrates we eat. However, some carbohydrates are better for fueling the brain than others. Highly refined carbohydrates and simple sugars are digested quickly and glucose floods the bloodstream rapidly resulting in a large, quick release of insulin to move the sugar/glucose from the bloodstream into cells. As a result, blood glucose subsequently drops sharply. If blood glucose levels drop too low (hypoglycemia), it not only deprives the brain of fuel, this lower blood glucose can trigger the release of counter-regulatory hormones such as cortisol and epinephrine/adrenaline. These hormones lead into a vicious cycle of craving more simple sugar foods to counteract the low blood glucose level. 4

Mood changes such as anxiety, irritability and hunger have been evidenced as potential effects of these fluctuations. Additionally, observational research has found that recurrent hypoglycemia (low blood sugar) is associated with many mood disorders. 4

Complex carbohydrates high in fiber, such as vegetables, fruit, legumes and whole grains, as opposed to simple carbohydrates, are digested much slower and support managing blood sugar levels and brain health.

Protein & Amino acids

Amino acids are the building blocks of proteins. There are 22 amino acids some of which can be made in the body and some of which need to be derived from protein in the diet (therefore called essential amino acids).

A single cell can contain thousands of proteins, each with a unique function. Protein is involved in the structure of genes, blood, tissue, muscle, collagen, skin, hair & nails, and a necessary component of all the many hormones, enzymes, nutrient carriers, infection-fighting antibodies, and neurotransmitters, plus more. Continuous cell-building and regeneration necessary for life requires a steady daily supply of protein throughout the day. 3

Neurotransmitters are made from amino acids. Some amino acids convert directly into neurotransmitters meaning that if the diet does not provide adequate amounts of these amino acids, or a deficiency occurs due to genetic or other lifestyle factors, sufficient neurotransmitters may not be produced, potentially leading to impaired communication between neurons. For example, a deficiency in certain amino acids may leave someone feeling depressed, apathetic, unmotivated or unable to relax. 3

To date likely the most widely studied in diet-behavior research has been the connection between tryptophan (an amino acid) and serotonin (a neurotransmitter). Tryptophan, found in eggs, lean meat, free-range poultry (especially turkey) and beans, is first converted to 5-hydroxytryptomine (5-HTP) and subsequently converted to serotonin. Adequate levels of serotonin are linked with positive mood, wellbeing and sleep patterns. 3

Another well-researched amino acid linking diet and behavior is tyrosine, found in avocado, cheese, cottage cheese, eggs, and poultry, which converts to dopamine then noradrenaline and subsequently adrenaline. Sufficient steady levels of tyrosine have been shown to improve mental and physical performance under stress better than coffee. 3

In addition to low protein consumption, there are various factors that also contribute to inadequate levels of amino acids such as genetics, stress, poor diet, hormonal dysregulation and environmental toxins.

Gut microbiome

Evidence indicates that normal central nervous system function is linked to healthy gut function. The gut is known to communicate with the brain through the release of hormones, neurotransmitters and immunological signals.

Diet alterations can have a significant influence on the gut bacterial composition within 24 hours; however, the microbiota composition will be restored if the dietary change is only short-term. There is no standard of a “normal” microbiome for the general human population as many factors such as diet, environment, health status, season have an impact. Scientists are finding, the microbiota composition in the gut is not significant, as long as a symbiotic relationship exists whereby the bacteria are assisting with vitamin and amino acid production, healthy immune tolerance and GI homeostasis. 5

The normal microbiome however can become, dysbiotic, when confronted with changes in diet, stress or antibiotics and other medications. This dysbiotic states often leads to increased gut permeability, allowing food particles and bacteria that are normally unable to cross the gut lining barrier to escape into the systemic circulation; this condition is often referred to as leaky gut syndrome. Strong evidence has been reported on the detrimental effects of increased intestinal permeability on the immune system and has been linked mental health disorders including depression, anxiety and autism. 6

Studies have reported that the use of probiotics in supporting a healthy gut microbiome have effectively reduced anxiety and depressive symptoms similar to conventional prescription medications. Additional research has also shown that consuming fermented foods and natural sources of probiotics such as yogurt, kefir and sauerkraut support gastrointestinal and mental health. 5

Vitamins and Minerals

Vitamins and minerals are critical for the health of the body. They are required in adequate amounts by every system in the body to function properly including immune function and metabolism as well as playing an essential role in the synthesis of neurotransmitters, hormones, enzymes and proteins. Most vitamins and minerals can’t be produced by the body and are constantly being utilized, broken-down, and excreted. Because most are not stored in the body in large amounts, regular daily intake is important to maintain sufficient levels.

As mentioned above the synthesis of neurotransmitters affecting mental health are dependent on sufficient levels of vitamins and minerals.

In addition, some vitamins work as anti-oxidants, which protect the brain from the damaging process of oxidation. Antioxidant rich food sources include blueberries, red peppers, leafy greens, broccoli, nuts and seeds. 3

Oxidative Stress

Oxidative stress results from excessive free radical production without a sufficient counteracting antioxidant response. Free radicals can be produced from a variety of sources such as smoking, alcohol, fried foods, stress, and environmental toxins. The brain’s high consumption of oxygen and high fat content make it extremely vulnerable to oxidative stress and increased risk of impaired brain functions and mental illnesses. 7

Oxidative overloads from any source can further cause mental disorders in sensitive individuals by reducing glutamate neurotransmitter activity at NMDA receptors in the brain by depleting levels of glutathione (GSH) needed for efficient NMDA function. 2

Further ways foods/substances can negatively impact brain function

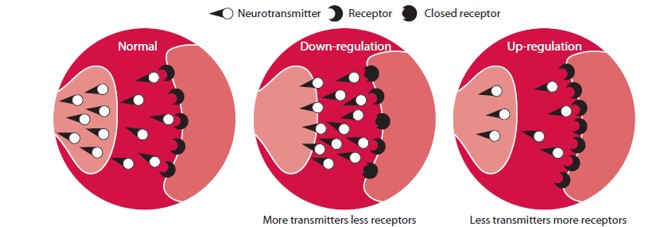

Some foods/substances are good at temporarily promoting the neurotransmitter that we lack and, as we crave and then consume them, they ‘trick’ us into feeling better, for a while. For example, if an individual is low in levels of adrenaline, they may find themselves craving caffeine, which gives a short-term boost to levels of adrenaline. Similarly, products containing nicotine trigger the release of GABA and dopamine, responsible for reducing feelings of stress. Chocolate is another classic example of this ‘trick’ effect: it contains substances that boost levels of noradrenaline, which subsequently boost our feelings of wellbeing and enthusiasm for life. 3

While there is perceived immediate psychological benefit of these foods/substances, the process can make the brain less sensitive to its own transmitters and less able to produce healthy patterns of brain activity as these substances encourage the brain to down-regulate. Down-regulation is the brain’s instinctive mechanism for achieving homeostasis. When the brain is ‘flooded’ by an artificial influx of a neurotransmitter (for example, adrenaline triggered by a strong coffee), the brain’s receptors respond by ‘closing down’ until the excess is metabolized away. This can create a vicious circle, where the brain down-regulates in response to certain foods/substances, which in turn prompt the individual to increase their intake of those substances to get the release of the neurotransmitter that their brain is lacking. This is one reason why people sometimes crave certain foods/substances. 3

References:

- National Institutes of Health (US); Biological Sciences Curriculum Study. NIH Curriculum Supplement Series [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Institutes of Health (US); 2007. Information about Mental Illness and the Brain. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK20369/

- Walsh W., Nutrient Power Heal Your Biochemistry and Heal Your Brain. Skyhorse Publishing. 2012.

- Cornah D, Van De Weyer. Feeding Minds, The Impact of Food on Mental Health. The Mental Health Foundation. 2007. Feeding minds: the impact of food on mental health | The British Library (bl.uk). Accessed April 2023.

- Firth J, Gangwisch JE, Borisini A, Wootton RE, Mayer EA. Food and mood: how do diet and nutrition affect mental wellbeing? [published correction appears in BMJ. 2020 Nov 9;371:m4269]. BMJ. 2020;369:m2382. Published 2020 Jun 29. doi:10.1136/bmj.m2382

- Clapp M, Aurora N, Herrera L, Bhatia M, Wilen E, Wakefield S. Gut microbiota’s effect on mental health: The gut-brain axis. Clin Pract. 2017;7(4):987. Published 2017 Sep 15. doi:10.4081/cp.2017.987

- Järbrink-Sehgal E, Andreasson A. The gut microbiota and mental health in adults. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2020;62:102-114. doi:10.1016/j.conb.2020.01.016

- Salim S. Oxidative Stress and the Central Nervous System. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2017;360(1):201-205. doi:10.1124/jpet.116.237503